The following are ~1000-word attempts to describe the current state of The UMC in a succinct manner that likely oversimplifies things with broad brush strokes. Nonetheless, they will be useful primers for newcomers to United Methodism, longtime members, or passersby looking to enter the conversation.

- How did we get here: Power & Polity versus People & Places (This article!)

- What happens now: General Conference 2024 (LINK)

- What future awaits us: Avoiding the Fundamentalist Future Trap (LINK)

Part I: Power & Polity

versus People & Places

United Methodism At-A-Glance

The United Methodist Church occupies a unique place in America and on the world stage.

The UMC is a worldwide, mainline, evangelical Church. It sits at the intersection between evangelical (baptists, etc.) and mainline (the Seven Sisters of Protestantism) movements, drawing the best elements from them both. It has a unique composition on the global Christian stage: progressive and conservative people together under a global democratic representative polity with episcopal governance.

At one time, it was the largest denomination in America—now it is officially third behind the Roman Catholics and Southern Baptists, although the LDS (Mormon) church probably passed us for spot #3 thanks to recent disaffiliations.

The Methodist tradition, which began in the 18th century, went through many schisms, reunions, branches, and offshoots before its largest entity finally settled on its current form, the United Methodist Church, in 1968. It’s right about then that we need to look back at two movements within the church that led to the situation in the UMC today.

An open table…eventually

A diverse church with many different traditions and shifting power dynamics must make good decisions regarding minority groups seeking equal treatment within the church. Prior to 1968, the UMC included minority groups in the Church and emerged better for it with both mainline and evangelical qualities.

Progressive, Moderate, and Conservative people worked together to advance the rights of women to become clergy (1956) and to fully include African American pastors (1968). Make no mistake, these were far too late and hard-fought to achieve, denying ministry to people groups for decades, and even when achieved, implemented incrementally. But still, we celebrate! Yes, there were Traditionalist groups that opposed the inclusion of women and black pastors, but by the dates of these votes, their influence was not the majority because women’s suffrage and black civil rights movements in civil society transformed the church for the better.

These two acts of inclusion made United Methodism the largest denomination affirming women’s ordination. And all of Methodism, especially Methodism worldwide, has benefitted from these two acts of inclusion.

Traditionalist Reaction to “Minority Mania”

But those two acts of inclusion of women and African Americans were too much to bear for the Traditionalist element in United Methodism, which began to organize to stop the alleged “minority mania” of an ever-expanding table of grace. Rather than leave the denomination like Alabama Methodists who created the Southern Methodist Church, they created their own shadow denomination within The United Methodist Church to weaponize fears of minority groups, particularly the LGBTQ+ community.

With the messaging foundation laid by the Good News Magazine (1966), The IRD (1981), and others, Traditionalists began creating a parallel reality within the UMC but outside of United Methodist oversight, accountability, or connectional leadership. Through the Mission Society ( 1984 parallel to the General Board of Global Missions), Bristol House Books ( 1987 parallel to Abingdon), and the RENEW network ( 1989 parallel to United Women in Faith), traditionalists created their own parallel structure that provided books, fellowship, events, and missionaries for congregations to support. Within these structures, Traditionalists had free reign over curriculum and theology. Leaders encouraged followers to contribute to their own causes instead of United Methodist ones, siphoning off money and organizing power to themselves.

This shadow denomination’s coordination and messaging have borne significant fruit within the denomination: every General Conference (the Congress-like doctrine-making body of The UMC) since 1988 has been a majority of conservatives, thanks to two acts of gerrymandering of the General Conference representation.

Traditionalists maintained their dominance until exiting their accumulated people, property, and groups from United Methodism during the 2019-2023 wave of disaffiliations even though their money and influence continue to remain active in United Methodism.

Carving out Breathing Space

While the Traditionalists were seeking power and polity control in The UMC, Progressives have been carving out places to save people’s lives.

Beginning with the Gay United Methodists caucus (later called Affirmation) in the 1970s, early acts of promoting the inclusion of LGBTQ+ persons, and continuing with the strategy of organizing congregations under the Reconciling Ministries Network, LGBTQ+ inclusion efforts are about proclaiming who and where are safe harbors for queer United Methodists. Also, by electing conference and jurisdictional leadership that reflect full inclusion of LGBTQ+ persons, progressives have grown top-to-bottom full inclusion in the Western Jurisdiction—and sizable majorities in the Northern jurisdictions as well.

This is significant because United Methodist polity places accountability and organizing at the local and annual conference level. The Wesleyan tenet of local accountability—enshrined, ironically, by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, when they merged with MEC in 1939 to ensure Northern bishops would not lead the South—meant that the progressive jurisdictions and annual conferences could continue their local practice of full inclusion of LGBTQ+ persons despite what General Conference legislates. Thus, traditionalists were perpetually unable to drive out progressives from The UMC.

The polity the Southern conservatives put in to benefit their own power created untouchable progressive majorities elsewhere, sizable places in United Methodism where full inclusion of all people is practiced and celebrated.

The Withering Storm around 2024

As we lead up to General Conference 2024, we see these two long-term directions reaching a tipping point.

- The majority of Traditionalists in the United States have left, the damage is done. What efforts will help United Methodism recover from the decades-long undermining of connections trust by Traditionalists?

- How will hoped-for acts of inclusion reflect a pre-1968 spirit of “better together” in the face of an increasingly polarized and go-at-it-alone society?

In our next article, we’ll examine what’s at stake and why United Methodists need to care for the General Conference happening in Charlotte, North Carolina, at the end of April.

Your Turn

Place and People are as important to Methodist ecclesiology as polity and doctrine. A denomination needs the energy of traditionalists and progressives alike to maintain the gains of its various movements, but cannot sacrifice minority groups on the altar of unity. As we lament what could have been, we need to be eyes wide open about how we got here, so we can better seek a common future together.

Thoughts?

Thanks for reading, commenting, subscribing, joining the WhatsApp Channel, and sharing on social media.

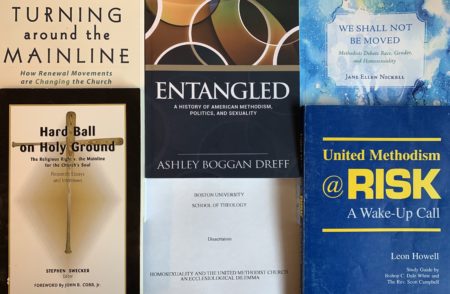

Is there a list of books/articles regarding “Methodist History Resources” you recommend? I have read a few books, but I wasn’t aware of those that appear in the graphic above.

You say, “thanks to two acts of gerrymandering of the General Conference representation”. The one I know about is changing to local church membership from laity and clergy numbers. What’s the other one? What should it be?

So damn smart and articulate. This is really helpful. Thanks, Jeremy Smith! Patrick Ferguson