Almost a year ago, we discussed the post “John Wesley thought the Creeds were Weaksauce.” In it, I contended that John Wesley did not see the Creeds as essential to the regular gatherings of the people called Methodists. Now a year later, I have some more to contribute to the discussion.

Dr. Raymond E. Balcomb was pastor of First United Methodist Church in Portland, OR, from the 1960s to early 80s (full bio here). The following is an edited form of a longer sermon he gave in 1966 in response to questions about why that church didn’t recite the Creed every Sunday. It is reprinted with permission of his family.

I invite you to consider his argument that our words should match our actions and that our actions are more important than our words.

====

Why Don’t We Say the Creed?

A creed gives a firm outline to one’s thinking and keeps it from becoming just a formless blob of believing in everything a little bit. The Apostles‘ Creed, although seldom if ever used in the Eastern Orthodox churches, and although its exact wording has never been established by a Council, probably comes closer to being universally acceptable among Christians than any other post-biblical formulation.

As such it tends to unite us and to provide a means whereby we can identify one another and, even in a strange land or an unfamiliar place, feel at home in the community of believers. Its regular use gives a “clear opportunity for the people with one voice to declare their Christian position.” It has never been the center of any particular controversy, as some of the others have, so there is considerable room for varying interpretations.

Still, there is no Creed in our service this morning; there was none last Sunday and it is not likely that there will be one next Sunday. Why?

The Creed is not an adequate summary

First of all, it should be noted that the Apostles‘ Creed was not developed for use in public worship. Such usage comes’ from the Middle Ages and carries no particular weight as “traditional.” So far as the oldest tradition in the Church is concerned one might better ask “Why do you use a creed in your service?” rather that “Why don’t you?”

The Creed was never intended to be, and is not, a complete or adequate summary Christian doctrine. The Creed is no more an adequate statement of faith for an adult Christian than a primer is adequate reading material for a college graduate. It says nothing whatever about the Bible, the nature of man, atonement, justification, salvation, grace, prayer, or the life of ethical and other-centered love and service. It is at best a poor guardian of orthodoxy and could have been affirmed in good faith by many of the most famous heretics and schismatics of church history from Arius and Pelagius in the fourth century down to Servetus in the sixteenth and Joseph Smith (founder of the Mormons) in the nineteenth centuries. The tradition that it was written by the original twelve apostles is a pious legend unmentioned before the fifth century.

The Creed is just a part of that vast non-canonical literature of thought and devotion which has developed within Christianity across the years which may or may not prove useful from time to time in public worship.

The Creed no longer says what it means

In the second place will you note that it no longer says what it means. It has meaning, valid meaning, great meaning; but the meaning does not come through clearly to contemporary minds. It has overtones and undertones that most of us completely miss.

- Some of its phrases are statements of historic fact-—”suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified dead, and buried”

- While some are pure faith—“I believe in God, the Father Almighty”

- And still others are symbolic—he “sitteth at the right hand of God”

How to tell fact, faith, and symbol one from another is not always easy. It is possible, for example, to make a case for “born of the Virgin Mary” under any of the three.

The net result all too often is that the use of this Creed raises far more questions than it answers. One of the things that bothers a great many intelligent and sincere people, I would say, is that in church we seem so often to say things that we don‘t really mean, or to say them mechanically by rote without thinking of or knowing their real meaning; with the result that we are open to the criticism of being naive, formal, or insincere;

- Who among us here would have thought that ‘the phrases about Jesus which we commonly take to be definitions of his divinity were actually inserted into the Creed to assert his genuine humanity?

- Who among us has not had to have explained to him the difference between believing in the holy catholic Church and the Roman Catholic Church‘?

- Who uses a phrase like “the quick and the dead” anymore–except perhaps as a classification for pedestrians?

So far as I am concerned, the ancient Creed is a good deal like modern poetry or painting. Its meaning is not readily clear; rather than helping me understand, it hinders and confuses. It has meaning, and can be understood, but the effort for most persons is greater than they are likely to make. It is too far from the language of ordinary contemporaries to say to them what it means.

There are better alternatives to the Creed

The third and main reason is that there is something better to use. There is something which combines all the advantages of a creed with few, if any, of its disadvantages—something which provides a definite structure of religious belief, and gives the congregation an opportunity “with one voice to declare their Christian position,” and adds to it a guide for action.

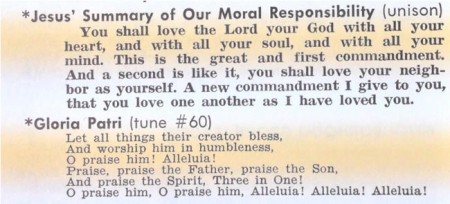

I am referring to what we recite under the title “Our Lord’s Summary of the Law.” It is better than the creed because it is older, more intimately associated with Jesus, and far more comprehensive and demanding. [Editor’s Note: The above scan is from a 1972 Bulletin where the section is titled differently than this 1966 sermon]

- The first phrase of this Summary — “you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind” (Mt 22:37) – quotes directly a part of the oldest creed in the religious world, the Jewish Shema (Deut 6:5). No one has ever phrased more felicitously or compellingly the fundamental affirmation of the religious person than do these words which are roughly 800 years older than the oldest form of the Apostles‘ Creed, were daily on the lips of Jesus, and which he regarded as the first and greatest of all the Old Testament’s injunctions.

- The next phrase of the Summary — “And, a second is like it, you shall love your neighbor as yourself” — quotes directly an almost ‘equally ancient part of the Jewish Law, Leviticus (19:18). Its characterization as second only to the first has the sanction of Jesus, whether or not he was the first to glean it from the trivia in which it stands and associate it with’ the Shema (cf Mk 12:28-34, Lk l0:25-28).

- And the closing phrase of the Summary — “A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another as I have loved you” — is from the Gospel According to John (13:34) where it is reported among the last words of Jesus‘ mortal life. It adds the necessary specific and concrete reference to what may otherwise be debatedly abstract: “what is love? who is my neighbor?”

Jesus‘ teaching and example give the Christian the answers which insure a proper understanding and interpretation of the older commandments. The Summary is better because it is older and is directly related to our Lord. But most of all the Summary is better than any creed because it deals with doing and being rather than mere believing. As such it is infinitely more comprehensive and also vastly more difficult.

Right Belief = Right Behavior?

Rightness of belief has never been enough to insure righteousness in behavior. As the little Book of James (2:19) puts it, “even the demons believe.”

- The crucial question is not your belief in God but your loving obedience to him.

- The crucial question is not whether you believe in the life everlasting, but whether you are living a life of eternal quality.

- The crucial question is not whether you believe in Jesus, but whether you are living like him — in the words of C. S. Lewis: “Every Christian is to become a little Christ. The whole purpose of becoming a Christian is simply that, nothing else.”

I would not be misunderstood. Belief is important, and surely has its influence on behavior. But behavior is more important, all-important; it is those who do the will of God, according to Jesus, who are part of his Kingdom (Mt 7:21, etc).

- It is easier to believe in Jesus than it is to emulate him.

- It is easier to believe in God the Father than it is to act like his child.

- It is easier to believe that Jesus is the savior of the world than to do something ourselves to save the world.

- It is easier to believe that the church is universal than to make your own church universal in its outlook and inclusiveness.

- It is easier to believe in the Holy Spirit than it is to be obedient to its promptings.

And it is behavior, not belief, which is all-important.

Why don’t we use the Apostles‘ Creed? It was never intended for use in public worship, it no longer says what it means, and our Lord’s summary of the Law is better.

“For Christ is more than all the creeds,

And his full life of gentle deeds

Shall all the creeds outlive.” ~ John Oxenham, 1913

Dr. Raymond E. Balcomb, February 27, 1966

First Methodist Church, Portland, Oregon

====

*drop the mic*

Thoughts? Comments?

What’s interesting is you talk about the Apostle’s Creed. Which is the creed probably most often used in Methodist Churches. However, it is the Nicene creed which is used Sunday after Sunday in most churches that use a creed (Catholic, Episcopal, Lutheran, etc). Interesting!

Of course you post this two days after I finish a series on rediscovering faith. We used the Niceane Creed as a starting point, but it looks like we could’ve dug a little deeper. Thanks Jeremy

Thought provoking sermon! The church I pastor had a confirmation class which I taught. I was stunned by the illiteracy of the kids (had just started there) and ended up using the Creed as a teaching tool. Which, I believe was the original intent of it. I preached a series about it and one of the things I emphasized is that we often simply mouth the words… Thanks for sharing!

Your more interesting question is “does right belief lead to right behavior?” My answer will surprise you give our vastly different theological starting points, but I would say “no.” That’s because most of our behavioral quirks come from the subconscious — we’re motivated and impelled to act in ways we can’t always control by forces we don’t understand. So it simplistic to say right beliefs lead to right behavior. There we go, UMJeremy, agreeing again.

Having said all that, the John Oxenham poem that concluded the sermon is pure 20th century drivel. It reflects none of the robust Christological thinking of Colossians & Hebrews but instead a naïve assumption that what Jesus DID is somehow separate from his identity. Nope.

I love it! And here’s a writer making a case for typically-non-creed-reciting churches to use it!

http://worship.calvin.edu/resources/resource-library/the-case-for-reciting-creeds-in-worship/

I am leading a series on our beliefs this Lent and encouraging people to write their own creed. Each week we’ll share in a different creed to test out how they feel or resonate. Apostle’s will be the first week, others the statement of faith from the United Church of Canada, something from the National Association of Evangelicals. . . I’ve done this in Bible studies before and it’s been really positively received. I hope the same holds true for a worship setting.

Wonderful and thank you.

The Summary is better than any creed because it deals with doing and being rather than mere believing. As such it is infinitely more comprehensive and also vastly more difficult.

Our Lord’s Summary of the Law

You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And, a second is like it, you shall love your neighbor as yourself. A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another as I have loved you.

Matthew 22:37, John 13:34

First, he is simply wrong on the origin of the creed. It was developed for use in public worship – specifically the public act of baptism. I won’t go into excruciating detail, but the Apostolic Tradition and the similar documents give us a pretty clear picture of the early development of the creed and its predecessor, the Roman creed. If he were talking about the Nicene creed, he’d be correct, but the Apostles’ Creed has its origin in an act of public Christian worship, and its use in baptism and in morning prayer very early on is well-documented.

Second, it is indeed difficult to make sense of the creed at times, but that shouldn’t stop us from using it. Rather, it should encourage us to be more diligent in our catechesis. Simply because the creed requires explanation doesn’t make it irrelevant. Otherwise, his suggested replacement is also inadequate, since Jesus himself had to give an explanation about who one’s neighbor. Simply because a full understanding is not possible for all (or even any) who recite it because, “the effort for most persons is greater than they are likely to make” is an indictment on our poor ability to teach people the creed, not the creed itself. You could make a similar argument about baptism or the eucharist, too: the true meaning of the sacraments are frequently misunderstood, and few laity have read “This Holy Mystery” or “By Water and the Spirit” in order to appreciate what we really mean when we participate in the sacraments. And, ordinary people wandering into a worship service might not really understand that we believe in the Real Presence of Christ in the eucharist. But that does not mean we don’t do the sacraments.

Finally, replacing the creed with something like the summary of the law again sets this false dichotomy between belief and action. “The summary is better than any creed because it deals with doing and being rather than mere believing.” The creed doesn’t ask us to merely believe. That is not its function. Its function is to give us a common ground on which to stand and to unite us as the church. Our belief will be impacted by what we do, and what we do will be impacted by what we believe. And, we can become more Christ-like when we understand more of who Jesus is, which means understanding the fullness of the Trinity as expressed in the creed.

Wesley responds beautifully here. I would add that the poem at the end and the premise that creeds are too specific (thus limiting) but some vague statement of belief in the new commandment are examples of 20th Century liberalism at its finest. It’s not surprising things like “spiritual but not religious” or as Kenda Creasy Dean put it “Moralistic a Therapeutic Deism” are so rampant today — it’s roots are found in the vagueness of 20th Century liberalism found in this sermon.

I’m all for mystery (probably more than most). But limiting our language whereby we learn to interpret that mystery (and thus open ourselves to being changed by it) is just bad formation. United Methodists are the denomination who championed spiritual formation first and foremost. Creeds help with this and so does mystery. But you don’t have to exclude one in order to include the other.

I remember, I once asked a group of Christians about the Calvinist rubric “TULIP.” A nice little acronym that post-dates Calvin’s death, and that certain segments of the Reformed movement use as basically a shibboleth to see if you are truly Christian– err, Reformed or a heretic.

One fellow said something interesting, and I’m sure I’m mangling his thoughts but that’s how they’ve arranged in my head:

It was perhaps a useful rubric at the time of the Council (Synod of Dort). And it was meant to be a basic outline, and not the fullness of Calvinist-inspired thought. Of course, since we people love to have our rules, our boundaries and our securities, it has since changed. It has morphed into a merely academic form. “Simply assent to this and the pain can end” in a manner of speaking. Think within your head: “Yes, this makes sense and I accept this.” It becomes a mark of in-and-out and a way to box other people. While it was meant to “guard” accepted belief, it was never meant to be the fullness of the accepted belief. But, things have since changed and perhaps debased, and now it has come to be seen as the “fullness” of belief. To the point where the words perhaps become meaningless (certainly within a large portion of their use). In other words, words that used to point TO a living reality have since been confused, and the words have become seen as the only living reality.

Of course we could get a bit Tillichian and say that when the Symbol (TULIP or the Creed) ceases to be seen as pointing to the reality, then it becomes idolatrous. Symbols are malleable and culturally-bound. They are meant to point to something MORE. This is also what Peter Rollins and Altizer mean when they point out that some churches insist that the “idol lives.” A mistaking of symbol for reality, and the attendant need to “fight” for the symbol as reality.

Since last year’s post came in response to my tweet, I thought I might offer a few reflections on the sermon by Balcomb: http://www.mattoreilly.net/2014/03/do-we-need-creed-in-dialogue-with.html

Input welcome, of course.

Input posted as a comment! Thanks for the engagement, Matt, though we differ on its quality 😉

Interesting analysis but with serious flaws. I’ll go section by section:

1. The creed is not an adequate summary.

a. The author mentions lots of stuff that is not explicitly stated in the creed, e.g, “the Bible, the nature of man, atonement, justification, salvation, grace, prayer, or the life of ethical and other-centered love and service.” In my view, most of these are implicitly touched on by what is explicitly stated in the creed. Also, I find the entire line of reasoning somewhat disingenuous given that the author recommends replacing the creed with a statement that provides even less information and context.

b. The author mentions that the creed is a poor guardian of orthodoxy since it could have been affirmed in good faith by “heretics and schismatics” such as Arius, Pelagius, and Servetus. Two points: 1) throwing the baby out with the bathwater is rarely a good idea; the fact that the creed does not address a specific set of heresies is little reason to discard it. 2) The author is again being disingenuous (or perhaps is just blind to his own “heresies”). Does the author truly not realize that his own theological “re-definition of terms” and assignment of historical events to the realm of symbology later in the article represent far greater “heresies” than those of the men he mentions as heretics?

2. The creed no longer means what it says.

a. The author states that the creed contains a combination of historic facts, faith statements, and symbolic statements and it is unclear which are which. This is a problem with the author’s beliefs, not a problem with the creed. All of the statements in the creed are intended as historical statements. I’m sorry that this causes conflicts with the author’s liberal theological interpretations, but it is the author, not the creed, which has stepped outside the bounds of historic Christian beliefs.

b. Based on the categories the author chooses to put the creed’s statements into (e.g., he leaves “rose again” off his list of historic facts), I fear that his argument for abandoning the creed is in no small part driven by his own desire to not have to affirm the statements he personally disagrees with.

c. The author states that the creed includes statements that require explanation. This is actually a good thing! I personally learned much and grew in my faith by having each of the statements in the creed explained to me. Who views it as a bad thing for folks to learn more about the historic Christian faith and even a little King James English along with it?

3. There are better alternatives to the creed.

a. That may be true, but the author does not provide a good alternative that clearly states the core tenets of the Christian faith.

b. What the author does suggest as an alternative (i.e., love the Lord Your God, love your neighbor, love one another) suffers from the same set of problems the author just used to argue against using the creed! 1) These are some of the most misused passages in the Bible over the last century! Without providing a clear explanation of what loving God, loving your neighbor, and loving one another really and truly means in a Christian context, you are opening up folks to be able to embrace a non-Christian “warm and fuzzy” view of “love” as radical tolerance of everything and anything. My fear is that that is part of the author’s intent. The real meaning of “Love” only makes sense in the context that Christ is coming again to judge the living and the dead. Gee, isn’t that in the creed? 2) This alternative leaves out far more than the creed leaves out. How could the author have missed this point?

4. Right Belief = Right Behavior

This is a weak strawman argument. I see this, again, more as a reflection of the author’s desire not to have to affirm those statements in the creed that he disagees with. Both right belief and right behavior are important. Without right belief, right behavior will not follow. Without right behavior, right belief avails nothing.

Thanks for opening a discussion on the creed. It’s a good discussion to have even if we disagree.

Interesting. I found this article in a search for those who believe the creeds have done more harm than good.

I believe the creeds divide us …in fact history proves that they divide us. The longer our ‘creeds’ (or ‘theologies’) get, the longer our list of denominations and splits and arguments.

Using creeds does not require us to read, interpret and act on the scriptures ourselves and in our own families and church groups, which leads to an unengaged, thoughtless, weak, second hand faith, as you have somewhat pointed out.

I believe it is far better to live as a community of believers with Scripture alone to form and guide us, united in the Spirit through love, and under the wise leadership of older Christians as is natural and the early church Way.

What are your thoughts on this?

people, as was clearly This leads to unengaged thoughtless Christianity, as you have said.

I find it interesting when I hear a critique of creeds based on their divisiveness. This is the purpose of the creeds – to divide between the true and false doctrine.

Christians have the responsibility and the mandate to test teaching of teachers and preachers. (2 Tim 4:3, 2 Peter 2:1, Colossians 2:8 and many others)

That is ultimately the fault of the argument presented in this article. Clearly the Creeds do not aid us in the purpose of doing works of love for the benefit of our neighbor (unless we count discerning true doctrine as works of love) but at the same time Creeds are statement of belief (“credo” from Latin = I believe) . And even the phrase “Creeds are divisive, let’s unite” is a form of creed in itself.

Ultimately whether they are explicit or implicit, published on a website/in a book or used in worship every belief system has creeds and is shaped by them.

Although they usually turn out after a promotion, one can make sure of

the info’s trustworthiness.

I’ve recently read two books by John Shelby Spong, which have revitalized my view of Christianity as something that doesn’t have to be tied to a pre-Copernicus/Galileo world view, as recited in my church every Sunday in the Apostle’s Creed. God doesn’t have to be thought of as a Father, for example, nor as Almighty. Certainly the concept of him “making heaven and earth” no longer fits the scientific discoveries since the invention of the telescope. Former eras/civilizations thought the earth was flat, that Hell was “down there” and Heaven was “up there”, both ideas no longer making any sense. And the Creed goes on to omit what I consider the most important aspect of Jusus, namely, how he lived. The Creed skips from “born of the Virgin Mary” to “suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried”. Wait! It’s his life that’s important. How he lived. What he did. How he helped others. How his love for all people caused him to live. Anyway, that’s what I think. Is there a denomination of Christianity that believes that?

What do you make of the statement on page 89 of _The Book of Worship_? It reads: “The Apostles’ Creed in threefold question-and-answer form appeared at least as early as the third century as a statement of faith used in baptisms and has been widely used in baptisms ever since.” Do you know something I don’t know about the veracity of this statement?