The following is an entry in the “Holding the UMC Hostage” series regarding a manifesto that encourages discontent laity in our largest churches to defund the work of the global United Methodist Church. Read the full series:

The following is an entry in the “Holding the UMC Hostage” series regarding a manifesto that encourages discontent laity in our largest churches to defund the work of the global United Methodist Church. Read the full series:01 – The Setting | 02 – The Blueprint | 03 – The Effects | 04 – The Conclusion

“Mission work around the world, whether it be a new university in Africa or bicycles for Cuban pastors, is the work of “the connection,” as opposed to the work of a single congregation.” – UMC.org

“Theologically understood, connectionalism is an expression of ecclesiology and mission.” – Bishop Kenneth L. Carder

The previous posts focused on (a) what is the history of churches that withhold apportionments (b) what is different about this proposal (c) what are the advantages and collateral damages associated with this proposal. We even had Andy Langford himself write a response. This conclusion does not incorporate any of Andy’s comments into it as I wrote it previously and decided to let it stand alone.

What is this really about?

Make no mistake: I don’t believe that Langford is focusing on smaller churches that don’t pay their full apportionment anyway. He is focusing on the big guys, the megachurches and large churches that pay large sums into these funds (apportionments are calculated based on membership and budget and the overall general, conference, and district budgets) and he is offering the laity of those churches a proposed method to defund the General Church without accountability to anyone. Given that many large churches run hot on issues and emotional on populist arguments, it is easy to see how a dozen or so articulate laity could defund these funds rather easily.

Several times in the document, Langford singles out two issues (other than a “lack of making disciples”) as being reasons for denying a church tithe to the general boards.

First, Langford suggests that all is not equal in United Methodism as the church outside the USA reaps all the benefits without paying much:

It is time for congregations within the United States to follow the example of United Methodist congregations outside the United States (over 42% of all United Methodists) who only pay general church apportionments to the Episcopal Fund and none to the other six general church funds. In 2011, 99% of all monies that supported the general church came from the United States.

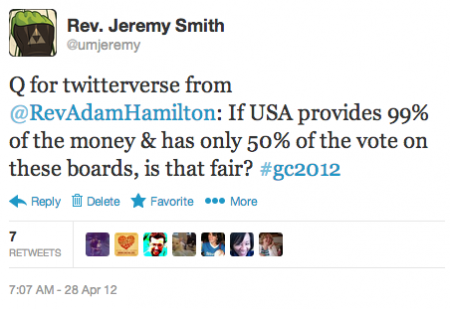

Langford is not alone in this frustration. During General Conference, while debating a church structure that would give more votes to the Central Conferences, Rev. Adam Hamilton asked the same thing while a particular internet-connected blogger was sitting in the room 🙂

To Langford, he has turned frustration over the Central Conferences getting more voice and votes at General Conference without paying more apportionments into an egalitarian “let’s make this all fair and burn it all down” scenario.

The second issue is one over trust as Langford asserts that money would be better given to people who the congregations know and “trust”:

Increasingly, many congregations believe that their monies are better spent on district missions and conference ministries and benevolences, the essential connectional ministries. These ministries are led by people known and trusted. These monies focus more so on creating and sustaining vital congregations and empowering annual conferences.

This is an appeal to familiarity. It’s hard to send a check to faceless people who do work that you cannot complain to their faces about. It’s easier to do that when you know and meet the Conference or District people and they ask for your support through these apportionments. While the General Church has done better in recent years to articulate exactly what people get out of their apportionment, information does not trump relationships. It even exasperates me to no end that the General Boards are not present at every Annual Conference or regional gathering showing how they are doing ministry.

While hard to argue against, all I can say is that the very Call To Action tenet that the Reformers embraced was “a lack of trust in the system.” To then exploit and exacerbate that tenet for one’s own ends is not really fixing the systemic issues, is it?

The World is Round, Not Flat

To both of these issues, I lament. There used to be a time when we celebrated these Apportionments. The growth our resources supported in Africa. The missions and development in our worldwide church communities. The growth of theological education across the globe. One of our own United Methodist women became the President of Liberia. Most of General Conference 2008 was celebrating these World Service Funded advancements…

…and then in a short 5 years these Apportionments are depicted as an albatross to the US-based churches that see their votes being taken away, their financial burdens increasing, and the resources for local and regional ministry feeling the squeeze.

I reject this blueprint paper and this movement to defund the General Agencies due to the following reasons:

First, we do not have a polity that allows for “opting out” of the parts of the Connection that we don’t like.The way the funds are bundled and the theological emphasis on shared ministry means that we are all in this together. Paragraph 247.14 states that paying the World Service Funds is the first benevolent responsibility of the church. The problem with pick-and-choose apportionment giving like being advocated in the previous posts is “Who decides what is and is not making disciples?” Who gave the local churches the authority to decide for the whole what was “making disciples?”

Second, the “smell test” for supporting general church work is one that most local churches would not pass–Langford’s church included. The smell test is that we should only be funding ministries that “create disciples” and not funding ministries that mostly “pay salaries.” By that test, the vast majority of our local church budgets that go toward clergy/staff salary and benefits would fail. Ought we dock the salaries of our administrative assistants or church custodians because they are not “making disciples?” By holding the General Church agencies to a different standard than one’s own local church is short-sighted and almost hypocritical.

Third, our Worldwide Covenant recognizes financial resources as well as other resources in our shared life church. What the United Methodist Church is struggling with is one effect of globalization (knowing where our money goes), and Langford repeatedly shows that the way the UMC is divided worldwide now is not fair. He mentions that churches and conferences outside the United States only contribute to one worldwide fund (the Episcopal Fund, which primarily funds bishop’s compensation). However, General Conference 2012 approved (with only one unrelated change) that our Worldwide Covenant amongst all of United Methodism recognizes more sources of mutual support than financial–though to some churches, only the money seems to matter. Here’s the quote:

In covenant with each other, we see each other as partners in ministry recognizing our gifts, experiences, and resources as of equal value, be they spiritual, financial, or missional.

By recommending defunding the Connection because the structure is unfair is a denial of this Covenant and a rejection of several theological tenets of the United Methodist Church. I don’t see how a local church can make this choice to defund General Agencies and yet have the same non-financially-equal-relationship with local groups or ministries. Although upon further reflection, usually those local ministries are ministries TO ethnic or impoverished groups, not ministries WITH that allows them to vote on ministry together. That higher-level of ministry that recognizes agency is one to which we are all called–and some will continue to reject both local and global versions–and to step back the UMC from this level of engagement would be missionally stunting.

Fourth and Finally, such an action is Congregational in mindset rather than Connectional. Clergy like Dalton Rushing took issue with Andy’s original UMReporter article stating that he did not want to be “accountable to a system that seeks 100% payment of financial apportionments for a dying system.” Rushing writes:

I am all for leadership–and God knows individual churches have taken difficult stands against the denomination in brave and courageous ways–but explain to me how withholding money from the general church does that? How does keeping MORE money for MY church in MY context show sacrifice? How does it do anything but assert the local congregation as the unit in the church with all the power, bishops and boards and district superintendents and oversight and theology and connectionalism be damned?

The drift in recent decades has been away from connectional unity towards congregational autonomy. Even as Langford advocates for us to pay for the Episcopal fund because we need bishops, I don’t believe bishops ought to be the only connectional glue. It removes an entire layer of United Methodism that is essential because without them, we have no upper connection. At their basic level, this is what those different layers of United Methodism are called to do:

- The primary purpose of the local church is to make disciples of Jesus Christ.

- The primary purpose of the annual conference is to provide excellent clergy to the local church.

- The primary purpose of the jurisdictions is to provide excellent bishops to the annual conference.

- The primary purpose of the general church is to do what the other bodies cannot do through pooled resources.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there’s a ton of Methodist ways to express disapproval. We can express our disagreement through conversations, through prayer, through speaking out against individual official UMC actions, electing people to positions of power to influence policy, writing petitions to General Conference, being elected to serve those meta-church agencies, refusing a bishops’ re-appointment, writing petitions and getting signatories…hey, we are a Methodist church and there’s a method to do almost anything, including express dissent. But withholding of apportionments–refusal to pay a tithe as a church–is not a Methodist way of doing things.

But reform is needed, this I agree. Langford’s words express the harsh realities that we must deal with…in appropriate ways. All the above are the Methodist ways of doing things. And we are not out of hope yet, despite the laments of the failed reformers of 2012:

- Reformers will tell you that they tried the Methodist way and it was struck down by the Judicial Council and thus reform was impossible. Yet one of the competing plans–the MFSA plan–did not make the Disciplinary error of conflating governance with fiscal authority that all the other plans did. Reform is possible.

- Reformers will tell you that they tried to fix the general boards but their lobbying stopped them at General Conference 2012. I didn’t see the Judicial Council–whose position was not threatened in the least by PlanUMC–being lobbying to declare it unconstitutional. If they found a constitutional way to change things, it would pass. Reform is possible.

- Reformers will tell you that the general boards are irrevocably broken, even though two of the longest running Board chairs are retiring. But boards matter and by jurisdictions sending the best people to be the board members, they can revolutionize entire agencies. Boards have that power, slowly and intentionally. Reform is possible.

Reform is possible and even with the worst possible lens, the General Boards’ time in the sun has passed. The writing is on the wall and if they do not do internal reforms and reorientation, then they may be significantly reorganized or reduced in 2016.

That’s the Methodist way.

That’s a connectional way that says we are all in this together, so let’s together figure this out not as congregations defunding out of protest but a unity of difference seeking a common mission together.

The Methodist way is a more excellent way. It’s a more connectional way. The withholding of the church tithe is a sign of creeping congregationalism that I believe is more dangerous in the long run, and I believe this movement must be exposed as detrimental to the whole of United Methodism and not the morally upright line-item veto that it is being painted to be.

Thanks for reading the blog. I hope you share it if your Finance Committee is considering this same movement.

Thoughts?

(Image Credit: “Clean Money” by flahertyb on Flickr, shared under Creative Commons License)

Well done series, Jeremy.

I’m especially motivated by your first line of reasoning. We don’t get to opt out of the parts of the connection we don’t like, and certainly not by unilaterally de-funding. I personally take great pride that the World Services Fund and Africa University Fund equip missions and ministry in places my little local ministry context couldn’t reach otherwise. I celebrate that the General Board of Church and Society advocated for large-scale justice in ways individual churches can’t accomplish. There are parts of our church and system and organization I don’t particularly like, and I express my disagreement in the “Methodist ways” you mention: petitions and legislation, running to be a delegate, speaking, preaching, blogging, tweeting, yes even a little civil disobedience. But not a financial boycott. Because I’m not trying to punish a corporation; I’m trying to change an organism of which I am a part.

I think that’s the big picture for me. This method of seeking change essentially removes a congregation from the connection its trying to change. I hope we can reform in ways that keep us connected. Nimble, flexible, vital, contextual. But connected.

Thanks for giving us so much to chew on! Peace, brother,

Becca

Still waiting for you to tell me exactly who our boards are accountable to? And it doesn’t count to say we send board members from Jurisdictions. Who do the boards answer to? I’m with you on the whole accountability piece but I only read a one-sided version saying local churches should not act without accountability — how do we address years and years of boards acting without accountability and consent from the people they represent?

One fascinating issue you’re raising for me in this series is just how absurd it can be sometimes to say “the General Conference represents the voice of the UMC.” How American of us to think a small body of elected delegates could actually embody the whole of the connection. The problem here with General Conference and the agencies is that the local level is forgotten or deemed unimportant in the grand scheme of things. In other words, we are WAY too top-heavy. I’m not necessarily in favor of Langford’s stance but I do find it compelling that he’s advocating for a stronger place at the table for local churches — after all, all ministry really local in the end.

Great series — I’ve enjoyed both agreeing and disagreeing with you through these posts!

@Ben G:

General Board accountability: Our general boards are accountable to their boards of directors. That is how all nonprofit organizations work (our general boards are all incorporated as 501c3’s); it’s how nonprofit law is written. We in the UMC have created a way of adding another layer of accountability via making the boards of directors accountable to General Conference. If we don’t like what the agencies are doing, our most direct avenue for influencing them is to try to get our jurisdictional conferences to elect us to them. The next level is through General Conference via its power to determine the purposes of our agencies. Each agency has a purpose outlined in their section in the Discipline. General Conference writes and rewrites this language.

The General Boards are not constituted to directly represent you and me. They are constituted to do what their boards direct them to do within the context of the purpose General Conference has set for them. When persons don’t like the way the boards of directors interpret those purposes, they can use the means available to them to try to get General Conference to add restrictions and/or more specific language to the applicable sections of the Discipline. That requires a concrete proposal (a petition to General Conference) and getting a majority of the delegates to agree with you. They have a lot of people trying to get them to do various things or vote in certain ways on specific pieces of legislation. In my experience, they/we listen to all of them (I have three times served as an alternate delegate to General Conference). But you be everything to everyone and do everything that everyone wants you to do. They have to make judgment calls, and inevitably, there are people upset by the collective decisions that General Conference makes.

The accountability of General Boards and Agencies is to their own boards, that is true. Those boards are elected by the Jurisdictional Conferences, supposedly to represent us. However, the process used to elect the boards is so opaque that it makes the election of the Catholic Pope look like a local town meeting! Who is nominated come from a back-room meeting (not smoke-filled, since we’re United Methodist). There are so many categories of race, gender, clergy/lay, age, disability, etc. that most of the energy goes to just finding people to fill the prescribed slots. The boards are not openly elected in a representative manner, so they do not effectively represent the grass roots of United Methodism. Thus, they are unable to fairly hold our General Board and Agency staff accountable to faithfully carry out the purposes set by General Conference in line with the thoughts and opinions of the grass roots members.

@Ben G

General Conference: General Conference does not represent the voice of the UMC. Nowhere does the Discipline say that it does. General Conference speaks for the UMC—a very different thing. Congress doesn’t need my consent in order to make proclamations and pass laws, neither does General Conference. However, I do have a representative in the House and two representatives in the Senate; I don’t get the sense that they do any meaningful listening to me. Pretty much any delegate to General Conference that I have met or spoken to, even though they aren’t actually specifically charged with representing me and even when they aren’t from my same Annual Conference, has been willing to listen to me, even to discuss the issues with me. Even if I weren’t getting elected as a reserve delegate to General Conference myself, I’d still feel that I have a great deal more influence there than it is even possible for me to have with Congress.

And that doesn’t even get into the matter that I can directly petition General Conference. Congress won’t be letting me directly propose laws, or even get a group of people to propose and submit a law, anytime in the foreseeable future.

Kevin-

Maybe I’m wrong but I was taught in seminary that the UMC does not speak unless it comes from General Conference because that is the only gathering where the UMC is truly together. The way(s) GC passes legislature and assigns the tasks of our agency is, in fact, the major voice of the denomination. But I suppose it all depends on how you look at it. Congress can act as representatives of communities but the truth is, once election, Reps and Senators largely live in Washington and are no longer apart of the local communities they represent. That distance is a tough reality when addressing local issues. The local issue at hand for many of us is that we sacrifice local ministry in order to be faithful to our apportionment giving because we’re told that’s what good United Methodists do. It’s past time that agencies and leaders on the top end of our structure understand that churches are suffering on the local level and it’s not a slam against connectionalism to expect that top-end to adapt and live with fewer resources as well. This is reality, not congregationalism.

Ben, agencies have been down-sizing for years. I worked at GBGM for seven years. They downsized not long before my tenure began. They down-sized during the middle of my tenure. They’ve just down-sized again. It seems like every time we had any kind of strategic discussion, we were talking about how to do more with less. We seldom really talked about anything we did without discussing how we could do it better, using fewer resources, in the future. In fact, toward the end of my tenure there, I managed a budget in excess of $1m. I cut it by over 9% while the programs it served expanded.

At that level, I don’t know anyone who isn’t sympathetic to the struggles of local churches. And they don’t just stop with sympathy. Off the top of my head, I can think of think of over half a dozen grant programs run by GBGM alone; those grant programs primarily funded local church community ministries that those churches wouldn’t have been able to fund entirely on their own.

But Jeremy didn’t start this as a conversation about the merits of apportionments and how they should be balanced against local needs, a concern that countless people are seeking creative solutions to. He started this as a discussion about Langford’s proposal around designating funding for some general church ministries and not others (whether that is for theological/political reasons or otherwise).

On that topic, my thoughts are somewhat complex. Our general church agencies straddle the line between nonprofit organizations and church government. On the one hand, they are incorporated as nonprofit organizations, and there are laws that govern how some of that works. On the other hand, they are part of a church polity, a church governance structure, sort of analogous to the way our various levels of civil governments have various departments (like Depart of Labor, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Federal Drug Administration, etc.).

Someone made an argument that just like when we give donations to other nonprofit organizations, we should be able to designate our general church apportionments. I think that is a bit like the argument that we should be able to designate our tax payments and be able to pay for some things and not other things. There are some compelling points in that argument, but at the end of the day, we can’t operate a government that way. We either pay for that structure, and use the channels available to us to try to change the things we don’t like, or we don’t, and we don’t have it. Our general church structure is much like that. These aren’t completely independent, autonomous organizations. They are part of a church structure. We either have that structure or we don’t.

I have my favorite list of nonprofit organizations that I can fund or not fund, and I can change which ones are on the list, and I can make decisions about whether to give designated or undesignated gifts. And that works; if a given organization doesn’t inspire enough support, eventually they will have to shutter.

But those are individual organizations. They are not part of a confederation of organizations that are structured in some way as to have an intrinsic connection to one another. They aren’t individual pieces of a larger whole. You can have one or not have one.

We have a general church structure because we are a denomination, and we have collectively decided that there are things we want this Church to do that our churches can’t do on their own. We are Methodist and we have created a structure. We are not independent congregations supporting, or not supporting, independent church organizations (and supporting one, like a mission agency, while not supporting another, such as a publishing house; or deciding that we no longer like the mission organization our friend churches have been supporting with us, so we are going to switch to a different one instead).

As an additional wrinkle, our apportionments don’t cover all the expenses of our general agencies. As apportionments get smaller, they have to develop more and more of their own fundraising efforts in order to supplement that income and be able to at least try to carry out their missions. This does give us an opportunity for designated giving; it just comes as something akin to “second mile giving,” but without the catchy moniker. I actually think this is a good situation. At the same time that I believe in paying apportionments, I also think that our general agencies need to embrace a little more of the nonprofit organization part of what they are and get serious about fundraising. I believe that as United Methodist churches, we should have apportionments, that they should be reasonable and we should pay them, and I believe our general agencies should fundraise, should get serious about selling themselves, communicating what they are doing, demonstrating the differences they make, and persuading us that they are truly providing value that makes it worth us supporting them individually beyond the required collective support.

The areas that support the work of the connection the least with their dollars are the ones who yell the loudest that everyone else needs to be connectional. That is simply hypocritical.

New England Annual Conference paid 80% of its apportionments last year.

California-Nevada paid 68%.

California-Pacific paid 81%.

Oregon-Idaho paid 74%.

Pacific Northwest paid 84%.

Yet, the amounts paid to the Advance by those conferences were more than the overall shortfall. If you are finding better priorities with your apportionment dollars, then how do you call anyone else out???

Creed-

With due respect, you’ve made the same points about 6 different ways on all four of the sections of this series. We get it — you don’t think folks in the WJ should gripe about how apportionments are treated because that jurisdiction is on the bottom-end of apportionment giving. But as a member of the SEJ — where we account for MUCH more of the apportionment dollars than you do in New England — please know that we get your point and don’t have to be reminded of it on each of Jeremy’s blog posts.

Jeremy wants everyone to be inflamed about Rev. Langford’s suggestion which is mechanically impossible in many conferences even if people were so inclined. Yet, many churches in those conferences aren’t paying their full apportionments. Jeremy wants us to major in the minors. If there was more dialogue about the larger picture, then I wouldn’t feel the need to add more and more facts to a relatively fact-free discussion.

I’m from Greater NJ and we have been paying our apportionments in full for a number of years. We sacrifice to do that. Acting like everyone should feel obligated to pay when the people who yell the loudest ignore the logs in their own eyes is foolish.

I have the strong suspicion that it makes it more difficult not easier to make the case to people in the SEJ who feel disconnected from the general church to meet their connectional obligations when others who profess to believe in those connectional obligations do not. Telling them “do as I say, not as I do” has never been productive. However, Jeremy’s few responses on those points are merely filled with snark.

Creed, do you think that being a troll on Jeremy’s blog is effectively making disciples of Jesus Christ?

a) Do you actually believe that this blog does anything to make disciples for Jesus Christ, much less effectively??? If that is the purpose of this blog, then we are really far from the boat.

b) If we change the definition of troll to “person who presents actual facts while disagreeing with me” then we have changed the definition in such a way to remove all meaning. Proudly saying that you will not engage in discussion with anyone who disagrees with you while saying you aren’t “feeding the troll” is the exact opposite of holy conferencing or even reasonable behavior much less tolerance for differing points of view. If your viewpoint is so weak that it cannot stand a factual discussion of its merits, then that should indicate the weakness of your position. I would expect that from a Fox News or Breitbart blog. Saying you and Jeremy accept those standards should not be a point of pride.

Advance funds are designated by the donors and pretty much just flow through the Annual Conference, with the Annual Conference having no say in that. So since they primarily come from individuals, and since apportionment funds come from churches (granted, that is still after the money has gone into the offering plate), just how many people, or what percentage, do you think are going to be sitting in their pews on Sunday deciding whether or not to give to their local church, where something like 2 cents of each of their dollars will end up as general church apportionments, or give to the latest UMCOR advance for Super Storm Sandy relief or some such?

Btw, while UMCOR is getting all this love, where do we think their overhead funds come from? Since 100% of Advance donations go to the designated cause (no cut of something like 15% that other organizations keep), the lights and heat have to be kept on somehow, the rent for the office space has to be paid, and the salary for the incredible staff that do all that wonderful work has to be paid too. Most of that comes out of apportionments–specifically the World Service Fund.

I’ve never done any meaningful research on what factors most influence how much of its apportionments a given church pays. Anecdotally, what I hear most often relates to their general financial stress, the struggle to keep the lights on, pay the pastor’s salary and fix the roof or the pipes. Unless you think that churches actually have a meaningful option of not paying those kinds of expenses, I don’t think they are often making the decision that some other use of their funds is a better use than paying their apportionments. While I have heard people on various finance committees ask what apportionments pay for, I’ve never heard, in a church that isn’t struggling to pay the bills, a finance committee decide anything along the lines of, “You know, we could use this pot of funds to pay our apportionments, but lets not. Have the worship and mission committees, and anyone else who wants to, bring back some proposals for something else we can spend this money on and we’ll do some of that instead.” With the one-time exception of someone who really didn’t get what it means to be Methodist and wanted that church (a church where I was a member when living in a different area) to effectively become congregational (and thus actually keep the funds within that local church and not use them for ANYTHING outside the doors), the only time I’ve ever heard talk of a conscious decision to not pay apportionments when the church had the ability to, it has been about disagreeing with some position an agency takes.

To reiterate, that’s not exactly a scientific study, just my experience, but I think your implication that churches in these Annual Conferences are simply making discretionary decisions to use these funds in other ways is missing the mark. I suspect there is much more to that picture. If I’m wrong, I’ll continue to use every opportunity I am given to talk about what are some of the things that are done with these funds, what they accomplish. I don’t think it’s only conservative churches that should pay their apportionments. I’ve just never heard what may be perceived as a “liberal” church talking about deciding to do something else with those dollars. The only time I have heard a conversation even sort of in this arena come up in a church toward the left end of the spectrum, it was after paying its apportionments, then having a conversation about picking out some Advance programs they could donate some more money to.

Actually, Kevin, I believe the overhead for UMCOR does not come from apportionments, but from our One Great Hour of Sharing offering.

There are a number of broader points that have been ignored in Jeremy’s fussilade. UM churches give about $250 million a year to causes outside the UM connection (direct benevolences). Some churches give more to those causes than their shortfall for apportionments.

As I repeatedly illustrated, a number of churches are contributing to the Advance (second mile giving) despite not having completed the first mile. The numbers I have are only those that were connected with a church. There is over $6 million contributed to the Advance that is not credited to any annual conference or local church.

Both of these seem to be problems of priorities or “will” or a lack of telling the story (interpreting the apportionments) or discontent (merited or not) with the decisions made by general church agencies with the dollars we entrust to them. I have gone to churches to communicate the message of what the apportionments accomplish and the need to give the first mile first. I feel able to do that in good conscience as long as I am also a strong advocate for making wise decisions transparently. Unfortunately, I have become less confident of that in the past few years.

I was on our conference council on finance and administration and am now on our board for camping ministries. In Greater NJ, we combine on the remittance form World Service and conference benevolences. So, when Jim Winkler makes another ill-advised pronouncement that achieves no useful purpose but annoys a lot of people, I see the effects on our bottom line for people who decide not to make a full effort to pay World Service but that also shorts conference benevolences as well.

I am a liberal Democrat who proudly supported Barack Obama in the February 2008 NJ presidential primary and remain a strong supporter of the President. But, much of what the general agencies do on the advocacy front seems to be more narcissistic in nature. It doesn’t change any minds. There is no real outreach made to the UMs who are Republicans who serve in Congress. That outreach would do a lot to advance goals that many of us share from Matthew 25, but it doesn’t happen because there seems to be more of an interest in being a “player” rather than simply being a humble servant in the vineyard on the part of too many who have the privilege of being paid with our apportionment dollars.

Thought-provoking series, Jeremy. I think Andy’s response shows some ways you may have misinterpreted his motives, leading to a harsher response than warranted.

My comment is that, rather than bemoan our lack of fidelity to connectionalism, we should try to build on it. If people give to relationships, rather than causes or programs, why not try to create more relationships between the local church and the work of General Boards and Agencies. I would favor cutting the board and agency budgets by 2/3 and then tasking them to raise that money from annual conferences, districts, and local churches. To do that, they would have to build relationships and effectively communicate what they are doing. If what they are doing does not get the support of local churches, the money won’t be there to do it. In the past, apportionments were a guaranteed income stream to the boards and agencies, which meant they could do pretty much what they wanted and ignore the local churches and members who give the money. Each dollar I give to my local church is a vote that I consider what they are doing important and worthy of support. I should get to vote for the general church programs in the same way–by financially supporting those ministries I believe are worthwhile. Most Christian ministries around the world and nearly all non-profits operate this way. Faith ministries seem to thrive in the current environment, while top-down directed giving ministries are struggling. But maybe that change is too radical for the UMC.

Thanks for your comments, Rev. Lambrecht. I recognize (and have said) that Andy comes at this from a place of honest faith and persistent concern (his first book on this was in 1992 with Will Willimon). I’m more concerned with the laity in the pews who would read a letter and assume it is a line-item veto defunding an issue when I’ve shown it clearly is not. Consider it a rebuttal to the paper and not the man behind it.

I do not share your solution of cutting their budgets drastically. As one person I quoted wrote, the Agencies are tasked with specific tasks. Why then would we defund their work such that their tasks would be unfinished and then hold them accountable for the lack of resources at the next GC? Like a local church ministry, we match mission with money support. Better in my mind is for jurisdictions to send serious well-educated delegates to these boards and remind the boards that they skated by in 2012 and they will be held more accountable in 2016. As Andy wrote in his response on this blog, GBOD is already making strides towards that relationship and hopefully the other agencies will as well.

I agree with the conclusion that reform is possible. However, it seems to me that the larger, more urgent question is “Is timely reform likely?” I have no doubt that, if we had 10 or 15 General Conferences to build support for organizational restructuring proposals, pass them, have them reviewed by Judicial Council, and tweak them to overcome the constitutional concern du jour, we might achieve reform. (Look how long the much simpler transition from Council on Ministries to Connectional Table took. It took us, what 3 General Conferences to change the Discipline to conform to an understanding of baptism that was no where near as controversial as any of the restructuring proposals.) So, if we have 40 – 50 years to make the necessary reforms, using the top down United Methodist way looks like a good option. If we are limited to that I will celebrate in heaven when those of you still outside the veil get it done right. But, it sounds to me sort of the like the last words of a dying church, “But, we have always done it this way.”

Thanks for the series Jeremy. It was interesting. Even Andy’s response shows that his heart is in the right place.

All of us who love the Methodist church want to do the best thing for it because we believe in it. I regained my faith in the Methodist church and give thanks for the Wesleyan witness in this world.

My take away remains that our identity is currently fractured. Lets face it, GC 2012 was a reflection of how deeply fractured and broken we really are. We have a motto in our stewardship in the local church: “Money follows Mission”. When we are clear about who we are, what we are doing, how we are doing it, and why we are doing it…money will come. When we are disjointed, doing many things, but none well, focused on 50 different things…money gets tight.

As a denomination right now, we are not focused, we are doing many things, we are disjointed. Multiple areas of focus, multiple visions over beliefs, multiple ideas of reform.

I would rather spend the next 4 years discussing, working, imagining, and focusing on who we are. This would lead to a real reformation in the church.

Okay, having read the entire series and all the comments, my mind is a little scrambled. I’m not sure it’s helpful to pick on specific general boards or persons or points in time. We find ourselves at a point in time when we are part of a denomination that wants to stand for something and to have a structure that makes sense. The problem is that it’s a hodgepodge of competing ideologies and loyalties, that more often than not do not find themselves united by Christ. This is reflected in various ways that your blog is often very adept at highlighting.

This monetary problem you highlight helps to note inconsistencies in many ways. Those who were in favor of centralization in the CTA are suddenly wishing for more democratic monetary conduct. Those who were against the CTA (you being one of them) find themselves arguing for conduct which favors the connection over the individual. Many wish to offer comparisons to governmental monetary policy, but we are easily corrected by remembering that governments put people in jail when they refuse to pay taxes but our denomination does nothing. I can’t pretend to be clear on the way forward. In many ways this series was great at helping people like me to explore the issues. I just wish you could have done so my caricaturing another’s perspective. I would ask for a more thorough counterproposal. I don’t have faith in the means of correction that you and Becca propose. Money speaks most directly and in ways that petitions cannot. I guess that’s what you’re experimenting with with Dream UMC. Let’s see how that goes and I’ll stand corrected…

Jeff, thanks for reading the whole series. I appreciate it.

I think the reversal is interesting. Though I would claim that my understanding of being connectional means not centralizing authority in a few (the Call To Action) or unilaterally taking authority for one’s self (this proposal). But in keeping with your comment, the church is constantly in this tension between connectional and congregational church…and our very definitions of what that means are to blame. In Langford’s response, he said he could not be congregational because he supported bishops–reducing connectionalism to appointment-making. I think it is broader. And in some ways, narrower.

It’s a tough balance and one where I fear the pendulum swings too far we have problems. Maybe in this corrective between two imperfect ideas there’s a proper balance. And when we find that proper balance, I’d be happy to be in the wrong.

Jeremy, You say, “It even exasperates me to no end that the General Boards are not present at every Annual Conference or regional gathering showing how they are doing ministry.”

But we need to be aware that this isn’t for lack of desire. They would be at annual conference sessions, and ask to be, but are regularly rebuffed. Why? Because we don’t value the time it would take. We want conferences to be short and feel they take us away from local ministry. It seems like a catch-22. Local churches bemoan. “what does the general church do for me?” while refusing to take time to participate in dialog requests or read material. A challenge from both sides of the relationship!