In United Methodist circles, all the rage a few months ago was to talk about the Death Tsunami: the passing on of the Greatest Generation and the retirement of the Baby Boomers and how that will precipitously drop the generosity and involvement of the laity in the United Methodist Church. FEAR.

In United Methodist circles, all the rage a few months ago was to talk about the Death Tsunami: the passing on of the Greatest Generation and the retirement of the Baby Boomers and how that will precipitously drop the generosity and involvement of the laity in the United Methodist Church. FEAR.

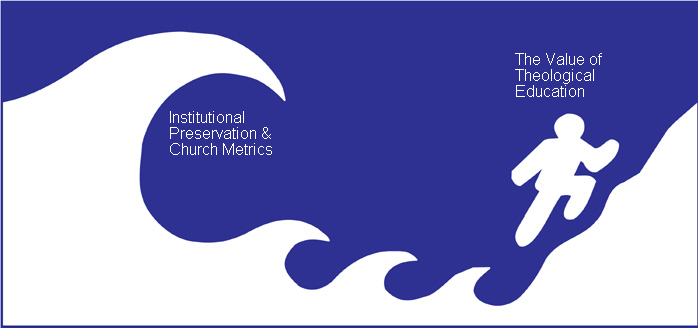

While I’m realistic about what effect finances has on churches, there’s other problems that are even more distressing to me. I think the real Death Tsunami will be the death of theological education for our clergy and church leadership.

And the plans are already in place and taking shape.

In Oklahoma, one of the Conference boards heard a presentation a few months back on the effect the financial situation of our churches might have on appointments. Since all most board meetings are open, this is public information and it’s okay that you read this. 😉

Because of the financial situation with health care costs and clergy pensions and the death tsunami, appointments might start to look like this:

- If your church budget is over $160,000, then you will likely be assigned an ordained Elder.

- If your church budget is between $80,000-160,000, then you will likely be assigned a Local Church Pastor

- If your church budget is under $80,000, then you will likely be assigned a Part-Time Local Pastor

In Oklahoma, we have ~550 churches. If this plan takes shape, let’s see where they break down on this spectrum.

- There are about 200 churches whose budgets are over $160k. That means the conference has need only of about 250 full clergy (given associate positions in larger churches…I’m an Associate over Student Ministries, for example). We currently have about 350 clergy, a ‘surplus’ of 100 seminary-trained clergy.

- There are about 100 churches with budgets between $80k-160k. This means the conference has need of about 100 local pastors. We currently have about 60 local church pastors, a need for 40 local pastors.

- Finally, there are 250 churches with budgets under $80k who would be served by part-time local pastors. Currently many of these are served by full-time clergypersons who have multiple-point charges, plus about 50 part-time local pastors. These appointments would be replaced completely by bi-vocational part-time local pastors, of which we need ~200.

Obviously, these are not hard-and-fast rules (the Bishops have full appointment power…and likely after GC will be able to dismiss clergymembers more easily), but they might become the general guidelines of what different-size churches can expect.

Why write about this? If I were a young clergyperson looking at this plan, here’s what I would say to myself: “Why Go To Seminary?” Local Pastors don’t need seminary and get health insurance, everything sacramental authority-wise that Elders get…and are in demand. Full Elders are expensive to local congregations, they have the cost of Seminary behind them…and there’s more Elders than Churches that can sustain them. Add to that the assault on seminary education by the arch-conservatives, and there’s little support to (a) get a seminary education and (b) become a full Elder until later in life when “they can make it, tiger” in the larger churches.

Maybe that’s okay.

Maybe a new focus on citizen-preachers who occupy their pulpits part-time during the week would make us more relevant and more authentic by mobilizing the laity. That’s what politics used to be: citizen-farmers who would serve in elected positions and then go back to the farm. The professionalization of politics and of clergy has an interesting effect on the church and society as a whole, so perhaps this movement back would be more effective and has shown in our history to be great for numerical growth.

John Wesley understood, of course, that education does not equal vitality, as he wrote “We would throw by all the libraries of the world rather than be guilty of the loss of one soul.” I’m totally with him on this point…take my library…as my books are mostly on my Kindle now. /snark

But I’m fearful.

I’m fearful for the UMC because theological education is incredibly important and, at certain points in our history, essential.

In our history, an uneducated clergy exacerbated problems between Methodists and Baptists. As John Beeson writes in his book John Wesley and the American Frontier, anti-intellectualism celebrated by passionate clergy like Peter Cartwright led to tremendous numerical growth but also a breakdown of progress of relations with other denominations.

An uneducated frontier Methodist clergy pretty much lost sight of Wesley’s middle ground between predestination and free grace. Wesley’s understanding of free grace may not have completely reconciled Calvinism and Arminianism, but it knocked off some of the rough edges of the controversy and allowed them to share common goals and work together. This middle ground was lost on the frontier. This author believes that this loss was largely because of an uneducated clergy in both camps and their simplistic approaches…an uneducated clergy was probably the biggest factor in the Americanization of Wesley’s doctrine of grace (page 78)

If we are called to the ministry of reconciliation, then a seminary education is crucial for this ministry. In our time of church conflict and decline, now more than ever being able to understand and reconcile differences and work together is an important ministry. Being able to piece together novel theological approaches requires not just passion but education. As I’ve written before:

- United Methodism is in the unique position amongst all the other denominations of being able to hold together unity in diversity (the last speech/bullet point on that page). If this is one of our calls, then we need to be equipped to handle it.

- This plan reeks of the No Church Left Behind sentiment behind the Call To Action where we are shifting seminary-educated clergy from small appointments to larger appointments (or out of ministry altogether) and removing them from small-church appointments. From that article:

This is what I’ve called “No Church Left Behind” (ala No Child Left Behind) where funds from under-performing areas are taken away and given to successful areas. As the CTA report says multiple times it is good that the church “celebrates success” but the flipside is that “abandons failure.” In other words, while it makes fiscal sense to redeploy assets, it abandons entire mission fields and programs and people instead of securing more funding to make programs more effective.

- Finally, theological education is more than doctrine, and if we narrow our theological education and remove even more young people from seminary, then even the seminary graduates will not be fully equipped to the ministry of reconciliation.

I strongly believe a spirit-filled but less theologically trained clergy may grow our church but will lose sight of one of the defining marks of Methodism, at precisely a time when we need reconciliation most.

Is this a diatribe against local church pastors’ intellectual capabilities? Absolutely not. One of my favorite Methodista bloggers John Meunier is a local church pastor (part-time, I believe) and he knows and reads more John Wesley than this seminary-trained full elder. There are hundreds others like him. Several of the most gifted people I know in my district are local church pastors (although many of them are seminary-trained). These are awesome spirit-filled people. However, I firmly believe each one would tell you that theological education is beneficial to ministry and gives you tools and experiences that you won’t get from self-education.

At the end of the day, a seminary education and being fully a member of a clergy ‘set apart’ group of people is an important calling. Why shouldn’t we be equipping, celebrating, and figuring out what other sacrifices we need to make in order to:

- Keep theologically-educated clergy in the pulpits of our most vulnerable churches and

- Keep Theological Education from being swept away by fears of institutional preservation?

Thoughts?

The same thing is happening in the UCC, Jeremy. There are too many clergy, too many graduates, and not enough full-time positions. Add to that the recent adoption of the idea of ‘alternative paths to ministry’, and I’m personally feeling like my M.Div, S.T.M. and very nearly D.Min are not valued by the denomination or its people.

When I got my call to ministry, I was unsure if I wanted to be ordained but I KNEW I wanted some sort of theological education. I cannot imagine entering ministry without seeking higher education in theology. I understand that for some, life circumstances and finances play a role in the decision, but there are many avenues to obtain it. If we go to a system where a master’s degree is not required, or discouraged, the ordination process is going to have to become much more rigorous regarding theology.

Overall, I think you’re right on the money. The loss of theological education in the denomination is frightening. I wonder if going to a flat salary (maybe by conference?) for all church clergy would be the way to go? Many other denominations have that policy.

A fine post Jeremy. As we have a world with greater complexity the church needs people who are well prepared for service in our mission field. We need education and educational independence, I know there are some aspects of my Seminary education that didn’t prepare me for parish ministry, but things like evangelism, preaching, pastoral care, and particularly my Bible classes continue to pay dividends everyday. I couldn’t do my job well without them. I see the need for reform in seminary education, at least how it was done at Boston U, but I couldn’t live out my call nearly as well as I am without what I received by having a generally rigorous seminary education in and outside the classroom.

At the Academy of Homiletics meeting last weekend in Austin, TX, Richard Mouw from Fuller (and chair of the Association of Theological Schools) did a presentation on the future of theological education, followed by a panel discussion. It was absolutely fascinating. The general consensus among the educators (or at least the 2 present and 2 former deans on the panel, with nods coming from the audience) is that we have an unsustainable model of theological education. While there will probably always be a place for seminaries, the number and mission of those institutions may well need to change. A number of proposals were offered, some of which were interesting. Heather Elkins from Drew University suggested an “itinerant professorship” in which profs would travel to offer short-term courses (with credit toward tenure, of course) in conjunction with Boards of Ordained Ministry, etc. Or, as I would suggest, you could make use of those of us with Ph.D.s or Th.D.s who are serving local churches to offer continuing education or other classes in our fields within a geographical area, contracted on an ad hoc basis with the seminary.

Point being, it’s not just an anti-intellectualism or numbers-driven issue from the local church or denominational angle. The problem is particularly acute in the seminaries and schools of theology themselves.

One of the things I really enjoyed about Methodism is the advanced education. It always kind of scared me when I’d see a church pop up somewhere because someone just decided to start one. Once I started learning about the process to become an elder, I really appreciated our system even more. It may be a very detailed, long, arduous process, but I feel some security knowing the process my pastor has gone through.

In this time of “economic hardship” or basically people aren’t tithing, I’m surprised the budget of a church would be looked at to determine level of preacher. I know a church that has a pretty decent budget, but has not been paying apportionments for years. I thought apportionments, not budget, were the problem. Some churches take great pride in having an elder. My husband’s first appointment was to a small church (budget was probably around $80,000). They were upset because he was not an elder even though he was in seminary and beginning the process. When they did not want to raise his salary a couple of times, he finally told them they would never get another elder because they weren’t meeting the minimum salary for an elder. Needless to say he got some raises and they now have an elder.

Most of the churches with budgets under $80,000 in my conference have local pastors. None that I know of are young (under 60). Perhaps it would change. Right now I’d say that goes against wanting to get “young, vibrant pastors” into our pulpits. Plus, I think the point is to not “waste” our young, vibrant pastors on small churches, but put them into our larger churches. If the young pastors did not go to seminary they would never appear in a large church. (I’m making assumptions around young pastors based on writings of Vital Congregations.)

If it’s only about money, we’re dead. Even the theological training of pastors in some churches is not enough to save us. We have watered down the gospel hoping to offend no one or to make it a gospel according to Heather, Jeremy, etc.; a gospel I can tailor to my wants, needs and sinful nature. The things I struggle with would be no more according to the gospel of Heather.

I do believe we’ve become lukewarm.

(I made a lot of general statements just for ease. I know there are exceptions and maybe I’m not giving churches enough credit and those that I consider exceptions are really the rule.)

Re: flat salary that Rev. Cooper suggested, I’ve heard the British UM has a system where all pastors are paid the same. Churches are then given a pastor who is more suited to their needs. Someone who is more suited for a large church can go there, but someone who is better suited for a small church goes there. I’ve seen many pastors in my conference who are better suited for smaller appointments, but because there is a mentality that bigger is better (more pay) they always move up. We’ve had pastors burn out and have major health problems that have caused early retirement that I believe stem from being a pastor better suited for a small church being in a large church. I suppose our pride and “this is the way we’ve always done it” has prevented us from asking for a smaller appointment. I believe it’s also why our bishops are never appointed back to a church and are forever bishops.

Great post. Good balance between the hard and fast economics of this and the pastoral/theological side as well. I’ve often agreed with the historical sociologists (Finke and Stark come to mind) that decline in a denomination can often be correlated with the greater amount of education/professionalization of their clergy. Nonetheless, I remain a big believer in the value of higher education.

One thought I had when reading this: we as a denomination don’t seem to be all that good at creating appointments. I know this is not necessarily the case across some conferences, but to me we seem as a denomination to lag behind in the church-start category. Church planting is risky, yes, and is not a solution to the bigger problem, but shouldn’t be ignored as a vital part of the solution.

Thank you for the kind word, Jeremy. I am a part-time local pastor.

A couple observations.

Many part-time pastors also serve multi-point charges, so your numbers might be thrown off on that front.

Our Course of Study — while not seminary-level education — does separate us from some denominations with congregational polity. And local pastors who are in Course of Study are doing so for 10 years, so there is a sustained and ongoing investment of time and energy.

In my conference, minimum compensation for full-time local pastors and elders is pretty close, so I would not see a big incentive to use LPs over elders, unless something in the pension and benefits universe is significantly different.

All that said, your number demonstrate why so many of our leaders are in a near panic about the future of the institution.

well stated john

You mentioned in your post that local pastors have full sacramental authority, and then used that to tip the scales against higher education/ordination.

Reading the Ministry Study for GC2012 reminded me that this is not necessarily the case. “In the case of extraordinary missional need, and where collaborative ministry among elders, deacons, and local pastors is restricted, the bishop may grant sacramental authority to local pastors and deacons. See ¶316.1 and ¶328 in the 2008 Book of Discipline for explanation of “missional need” for local pastors and deacons respectively.” Local pastors only have this authority through the bishop and only if there is not an ordained elder available to serve. The sacramental authority of our tradition lies with the order of elders and is passed on through ordination.

Knowing that missionally it is not possible to have an elder in every local church, the Ministry Study recommendation is as follows: “In addition, annual conferences, under the guidance of resident bishops, should be authorized to make allowance for sacramental practices based on needs within their geographic areas. The commission reiterates that local pastors’ presidential authorization is derived through the order of elders. Appointment as a local pastor should not automatically include sacramental authority. We expect local pastors to complete the Course of Study and encourage them to continue to move toward satisfying the requirements for ordination as an elder. No disciplinary revisions are recommended.”

I find that second to the last line especially relevant to your post… do local pastors desire to move towards ordination as an elder? should they? and what would be the benefit/drawback for them if they do? What would be the benefits/drawbacks for the church as a whole if local pastors completed those requirements and we suddenly had a lot more elders?

Katie, in practice, though, nearly every PTLP will have sacramental authority bestowed by the bishop because there are no elders who can take care of that. The church I started serving in July had not had Holy Communion about a year because it was being served by a supply pastor and no nearby elders could be enlisted to preside.

John, I find it problematic that no local elders were able to provide sacrament. If asked I would be honored to go to a church that is served by a local pastor to provide sacrament – quarterly at the very least!

Good post Jeremy.

Interesting take. Here in Tennessee, we only have one district where Elders outnumber Local Pastors, so that numerical imbalance you are talking about is already occurring. I attended licensing school as a seminary student, and the level of intentional ignorance and unwillingness to learn among the local pastors was downright scary.

Perhaps seminary education itself needs to evolve beyond the residential seminary/graduate school model that most of us experienced. There was an interesting discussion over at Patheos among Tony Jones and some others (http://www.patheos.com/Resources/Additional-Resources/Is-It-Time-to-Write-the-Eulogy-Frederick-Schmidt-03-21-2011.html) about that very idea, leading clergy to be more deeply rooted in their communities, something our current model of itenerancy hinders greatly.

Wow, Matthew. My licensing school experience was much different.

Not every pastor agreed with the theology as it was being presented or accepted every bit of wisdom, but I did not find my classmates any more resistant to new or different ideas than most adults I know.

Many of them did struggle with the “school” aspect as they had not had any formal schooling in some cases for 30 or 40 years and they were not — for the most part — ever likely to take part in a graduate-level course.

But I have to say the local pastors I have known have been deeply serious about their call and the work of ministry. Some of them are as stubborn and prideful as anyone else, of course, but I did not find that a particular disease of the local pastors I’ve known.

Matthew, as a woman, I fear that allowing churches to hire/call pastors would limit my ability to serve as a pastor in the UMC. I also feel like I have a great deal more freedom to speak truth and be prophetic in the pulpit thanks to our system. Just my 2 cents.

As a young local pastor, I know theological education is important, and in a perfect world, I’d be all for it. However, I cannot see the benefit of saddling myself with $80,000 of student loan debt in this economy when I can do the same job for practically the same money as a local pastor. I hope to be an elder some day, but I see no reason to do so until I’ve finished raising my children. Furthermore, I am not mandated to itinerate as a LP, which means my kids get to finish school in the same community they have grown to know and love. If you really want to solve these problems, we need to put itinerancy on the table and empower local congregations to hire their own pastors. Bishops having sole authority worked 300 years ago. We don’t live in that world anymore.

not being disrespectful, chris, but we really do not “do the same job”–our “job” is limited to our appointed parish only–much different than the broader ministry of seminary-trained clergy in full connection–as chair of the fellowship of local pastors/associate members in oklahoma, i encourage our local pastors to not be too comfortable with your view of itinerancy–the role of local pastor is constantly changing and we do not know what the morning will bring, so i offer you the same encouragement–and the last thing i would suggest for the future of our church would be introducing a congregational polity–blessings on your ministry

Amen. I am not interested in setting our church decades back by moving to a congregational system. Connectionalism is at the heart of who we are as Methodists. It’s part of the reason we have been so historically progressive (appointing women and minorities when a church would only have chosen a middle aged white male — which is still true). I don’t think we’re on the front lines of progressivism anymore, unfortunately, but a congregational polity would take us farther back than we ever imagined.

We can start by not calling it “connectionalism.” The word has no meaning. Catholics, Orthodox, Anglicans, Lutherans, and Presbyterians call it “being the church.” “Connectionalism” only has meaning over and against “congregationalism” which has simply never been the way in which catholic Christianity has understood itself.

Thanks, Jeremy, for a very balanced and thoughtful post. As the new church director for the NC Conference and a clergy member (Elder) of the Bd of Ordained Ministry, I find myself not alone in spending significant time reflecting on this issue. We are perplexed by the success of Local Pastors, especially PTLPs, compared to an overwhelming number of Elders in our Conference. The Board certainly values theological education as central to forming one’s readiness for ordained ministry. In my new church work, I can more easily see another side.

By necessity, launch approaches today are more missional than attractional. Missional communities are working to reach the 60% of the culture who have already decided they will never come to any church. This highly relational approach shifts the body of acumen needed for ministry effectiveness among pastors. It also forces a more equal distribution of the 5-fold ministry offices per Eph 4. Those Offices for that last two generations were collected and held by the ordained. Laity were allowed to help.

By necessity, I believe PTLPs in established churches live into a similar mode of ministry. Here, we have examples of unprecedented growth in some of those smaller established churches led by a PTLP. For example, one church with only a remnant has grown from 7 to 200 in 2 years, from one family to multiple multicultural families including Caucasian, African American, Hispanic and Native American. This was not the result of transfer growth. The body of laity there simply works very actively alongside the pastor as apostles, prophets, evangelists, shepherds and teachers. While the pastor is the the lead in these offices, he has no problem letting others be empowered to serve also. My concern and hypothesis is that their growth will slow down as he goes full time there. After all, he will have to justify a full-time position.

Two issues seem evident: 1) full-time pastors, whether Elders or LPs, can unconsciously inhibit shared ministry with laity, stifling the potential for a movement; and 2) Local Pastors (full or part time) are usually closer to the mission culture and therefore more relevant in the “Practical” part of Practical Divinity.

Jeremy, you bring out an excellent point, what about the “Divinity” part then? I agree with the concern. The last thing we need is any sort of dumbing down that could lead to a doctrinal quandary like the one you illustrated. My push back, however, is that schools of theology have done the same thing. An example being the tension between realized and future eschatology, which has leaned more heavily to realized than future. The doctrine of an ending age with a new heaven, earth and new Jerusalem descending from heaven has been demythologized and considered more of an evolutionary result of justice. How are we to “Be perfect” as Jesus said, knowing He also said we will always have the poor with us? Realized and future eschatology is actually at the heart of our UMC crisis because it’s so difficult to balance. Potentials for theological convolution exist in both the highly educated and uneducated.

In our new church work, the greatest problem we have isn’t a salary gap. It’s a culture gap. We have theologized our way out of relevance to our own “Jerusalem” and “Judea” (Acts 1:8). We need missionaries primarily, not pastors or theologians, to serve even our little rural family churches here in the Bible belt. More than ever we need theological education to support the primacy of discipling culture and missional living.

I’m excited to hear talk in theological education circles of a new didactic: a new missiological or praxeological approach, where theological disciplines are taught through practical courses. That’s a 180. Oh, if every one of our church planters and established church pastors could be missiologists!—trained theologically through real-world environments, this could connect the dots. And perhaps we could have a balanced Practical . . . Divinity.

Jeremy, thanks again. I appreciate your perspective. I’m a double-E in my undergrad work—another techie turned …”missiologist!” Lol!

Dang. Wish I’d read this 5 years ago before I started seminary. May have not made much difference because I’m glad to have the education but also have the bill now for my MDiv and the dicey prospect of entering full time ministry with a ‘glut in the market’. I’ve been a ptlp this whole time and tried talking with my district about bivocational ministry as an Elder. Currently, that is not a possibility but hope it will be in the future to allow full Elders to serve churches that could not afford them otherwise and bring our possibilities for ministry into greater contact with the world. Never heard the term citizen-preacher but I really like it.

Jeff writes “We are perplexed by the success of Local Pastors, especially PTLPs, compared to an overwhelming number of Elders in our Conference” but then goes on to give good reasons why it should not be perplexing.

I’ve had both seminary and legal training and would observe that neither do the best job preparing one for the profession. Law school prepares one to work in an appellate field, but generally does little to help one practice law representing real people.

I suspect that the Local Pastor mindset tends to operate more in the original model of discipling and enabling than the seminarian mindset does. Odd.

And, to touch on a really touchy subject, the Local Pastor might have more motivation. Pastoral burnout has always been a problem and never more so than today on the one hand, but those of us in the business world often wonder what many pastors actually do all day. . . .not that the job is easy or can be done “by the clock”, but many pastors with “tenure” just don’t seem to do much except prepare the sermon(s), plan the services, and chair some meetings, while many of those that never seem to stop going just don’t seem to get much done. In addition, it is not surprising that the itinerancy system enables promotion through tenure and politics, but those results can certainly be disconcerting to a layperson when we look up some years and see what we’ve been sent as pastor.

I don’t mean to be critical, and I’ve violated my own rule that one should always have some suggestions before pointing out problems, but I’m happy to read that you are discussing these issues and attempting to act positively.

Jeremy,

Several Boards and other leadership groups have heard a presentation about a possible future for pastoral leadership in the Oklahoma Conference which sounds vaguely like what you are referring to in your blog.

But contrary to your interpretation, the presentation was in no way an attack on theological education for clergy and church leadership. In fact, the role of the seminary-educated Elder would be enhanced in this model.

Nor is the issue institutional preservation. And the driving force has nothing to do with a “death tsunami”. The issue is the call to make disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world.

The original question asked was, “How many Elders will the Oklahoma Conference need ten years from now?” Rather than answering the question the traditional way, by simply estimating a replacement for the retirements and other exits over the coming decade, the question was rephrased: “How many Elders (and other categories of pastoral leader) does the Oklahoma Conference need right now?” Based on the assumption that a healthy church should spend no more that 50% of its annual expenditures on its pastor and other paid staff, it was determined that in Oklahoma, a church that annually spends less than $80,000 can’t really afford to pay a full-time pastor, based on the minimum salaries and benefits established by our Board of Ordained Ministry.

Next, the group asked a “What if” question: “What if every church got to have their own pastor, and paid what their church could healthily afford? What kind of leadership would that require?” That led to research that identified that of 529 churches in Oklahoma, 249 of them cannot “afford” a full-time pastor.

The next step was to test whether churches actually desire to have their own pastor (they do), and whether pastors would prefer to serve one church at a time, rather than two or three (they would).

Research was also submitted that part-time local pastors, properly deployed, have been effective in “growing the church”. Although worship attendance is just one possible indicator of vitality, 57% of the churches in Oklahoma served by part-time local pastors have a larger average worship attendance today than they had five years ago. This compares to a Conference average of 34%.

Also, even in our smaller and more remote churches, we can often identify competent, trusted, creative, dedicated United Methodist laypersons who are employed by the school, on the ranch, in their own businesses, etc., who have never thought of themselves as being able to serve as a part-time pastor because the only model they have ever seen is of a full-time, set-aside clergy.

Clearly, to raise up, equip, deploy, and mentor 250 part-time local pastors over the next decade would significantly change Oklahoma’s current way of doing things. Would it be worth the challenge? What would it look like to equip these people for leadership in making new disciples and in helping grow existing disciples ever deeper in their relationship with Jesus?

The current proposal includes a two-year Academy in specific practical categories, with the filter of disciple-making and disciple-growing at its heart. For example, the “Preaching” class might be, “How do you communicate the Gospel in a way that makes and grows disciples?” A team of leaders from the Board of Ordained Ministry, the Cabinet, and the Conference group that deals with leadership are collaborating on a possible curriculum. In addition, it is envisioned that each part-time local pastor will also be part of a monthly, ongoing small group that meets in a nearby town, led by an Elder or Full-time Local Pastor who has demonstrated fruitfulness in disciple-making.

This in no way takes the place of other theological education for these individuals. Hopefully, many will be more hungry than ever to grow in their own faith and understanding. And in Oklahoma, it is possible that this will be a place where some of our younger people can get a taste for ministry that will enable them to discern a call to full-time, set-aside ministry and seminary. It is hoped that this will be a real partnership among lay and clergy leadership groups in the Conference.

Of course, even if the idea works, it will never be “pure”. There will always be a need for shared ministry situations. But many who have actually heard the presentation are excited about the possibility of raising up a considerable number of indigenous United Methodist leaders from among our best faithful laypersons, and equipping them to lead the church in places where they live and work, and where our current model is not working.