I was a religion major in undergrad, and thus ever since the late 90’s, I’ve wondered why why the stuff I learned in religion school is rarely reflected in the pulpit? Are preachers scared to tell the congregation that the Apostle John didn’t write the Gospel of John? Or that Ash Wednesday originated as a pagan holiday? Or that believing God has a purpose for you is determinism and not really under the rubric of Wesleyan freedom?

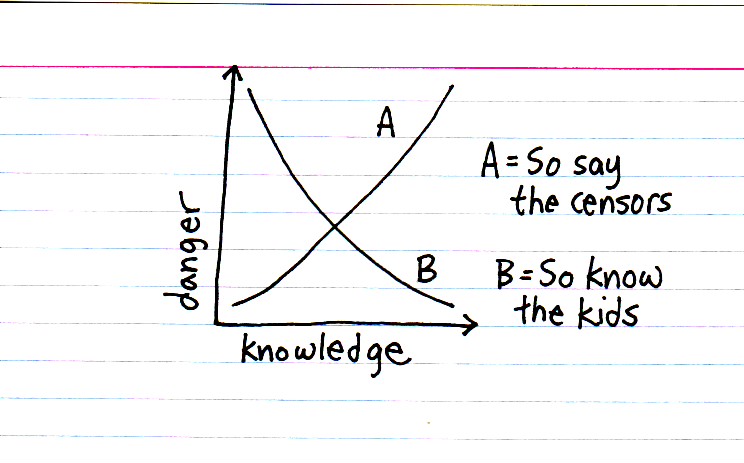

While musing on this censorship of biblical scholarship, I ran across Jessica Hagy, who posted the following as a simple condemnation of censorship (hat tip: Friendly Atheist):

It makes me wonder if this is that simple.

- The preacher (or Sunday School teacher) doesn’t impart 80% of her/his knowledge because it is dangerous and “faith-shattering” to know all this stuff without a framework (ie. control).

- The children (and learning adults) in the pews feel it is more dangerous to not know and thus be dependent on the pastor to interpret things for them (anyone remember the Reformation?).

What a simple illustration that depicts a tension I noticed as a student and now try to overcome as a preacher myself!

Thoughts?

Well. . .I have no thoughts other than this question has continued to bother me for a long, long time. Don’t really know how to “fix” it. Don’t really know where to start either…sigh.

Jeremy,

some links to the “censored material” you mention would do something to do more than sensationalize and continue the effort to “censor” either by commission, or in this case omission. Besides, some of it may be new to some of us, and we want to know more. I’m not the type to shy away from knowing more.

Peace,

David

I think there are several reasons why:

1. Fear of Congregational Reprisals

2. Lack of respect for congregation’s intellect

3a. Traditions

3b. Coupled with this could be a particular vision for the church or society, nostalgia for the lost time e.g. When America was properly Christian; When participation in the Mainline was the cultural norm, etc. These desires may exceed or render moot other explorations.

4. Theistic religions allow people to cast their existential and quotidian anxieties upon the Godhead. Who cares about that other stuff? I’m just trying to live and deal with my daily tragedies here.

5. I think it is surprisingly hard to persuade people, perhaps even the educated pastor, that religion is not a form of magic.

Revealing the human fingerprints and sociocultural stains all over the Bible mitigates its use for this purpose. (How does this help me get to point #4? How can I invoke one of “God’s promises” if the author was just responding to a competing group within the community?!?!)

6. God, properly portrayed, is strange, terrible and aweful (in the slightly archaic meaning of those terms). God is almost never portrayed this way, except in the fundamentalist/evangelical manner to indicate humans’ moral depravity and moral distance from God.

Why? Because if you say God loves everyone and then read the newspaper, then What the Hell does love mean? What kind of being or being-beyond-being is this we are dealing with? Well God-is-with-us in the Christ. WTF?

And I think working that out is extremely difficult. Too often it gets oversimplified, bastardized and totalized into an economic metaphor about sin/redemption.

But if we’re in the imago dei, affirmed that being human is not a wretched way to be vis-a-vis God by the Incarnation and Christ is present in those around us in community and in those we reach out to in love and service then what does that mean about God if this is in the foreground instead of all this you-are-a-sinner stuff?

Suddenly, Christianity at least, is not magical. It becomes a very human and humanistic enterpise emboldened by the example of Christ and set against the mystery of a God whose Kingdom is somehow within and among us.

I think getting a congregation to embrace the liberating weight of this requires a lot of work. So just tell them to be good, say sorry for their sins, Go Jesus! and sing and pray to ameliorate their earthly anxieties.

And that’s the best I can do in ten minutes at lunch.

–Josh A

You mention children, which is something I think about a lot. If we’re have a liberal and critical faith, what do we teach the children? Do we feed them simplistic (verging on wrong) things and correct them when they’re older, or do we somehow start with a liberal-critical understanding, and if so, how do we do that in an age-appropriate way?

I’m with Stephen here, and think a lot of this starts with the education (or lack thereof) we give children in the church. With my own daughter, I struggle with this. Explaining death to a four-year-old is tricky, because I don’t want to just say that her grandpa is “in heaven” and encourage her to think about heaven as a place up in the sky somewhere. On the other hand, I can’t quite tell her yet that her grandpa exists in the eternal mind of God, either (And when she asks why Jesus can’t come to her birthday party, oh goodness. I’m afraid I made Jesus sound a lot like Santa Claus). The education has to grow up with the kids as they become teens and adults and older adults. If they stick around not just the church but the educational pieces too.

I feel like I don’t have enough *time*. Isn’t that awful? In ten or fifteen minutes, with sixty people at various levels of faith and cognitive development, I feel like I can’t possibly convey the richness and complexity I want to. On my bad days, this means I end up really preaching, um, nothing. Nothing of substance, because I won’t give shallow platitudes and I can’t develop deeper discussions. On good days, I work some stuff in.

I think the remedy is not in the pulpit, but in the bible study, the visitation (the blog!), the one-on-one interaction with the congregants. And there again, I feel pressed for time. How many years will I be in this appointment? How long to I have to get to know a person and where they are and share with them some of where I am?

BUT, my seven years (I was a philosophy and religion major in undergrad too) of theological training were not a waste, and I do use them all the time. When I know exactly what I believe on a complex theological question and can articulate even a portion of that in a relevant moment (“pastor, is my brother who killed himself in hell?”), I know it’s a darn good thing I have a theology of Grace.

Hey Jeremy,

Good post–my tactic is to always be truthful. For example, last night for ash wednesday I preached on why I decided not to take the crucifix that had been hanging in the library over to the Catholic church as some members had suggested on our “church cleaning day.” Explained that I don’t really feel compelled to convey the Gospel in blood atonement theology, but perhaps we can take the truthfulness of the crucifix to heart in other ways during Lent. We should also confront our squeemishness about looking at the crucifix with its blood and gore, yet being more than happy to sing “Victory in Jesus” and other hymns that speak of being “bought,” “ransomed,” and “plunged neath the cleansing flood.”

As far as speaking about challenging ideas from the pulpit or in a Bible study, I always followed my dad’s advice that “people don’t care what you know till they know that you care.” In other words, develop the relationships first. I’ve always found that after churchpeople get to know me, they are excited to find out new ideas about scripture, theology, and whatnot.

I recently came accross your blog and have been reading along. I thought I would leave my first comment. I dont know what to say except that I have enjoyed reading. Nice blog. I will keep visiting this blog very often.

Elaina

http://www.craigslistpostingtools.info